© 2024 - In memory of Francesco Bissolotti in the 5th anniversary of his death

Francesco Bissolotti, father and teacher

byMarco Vinicio Bissolotti

Cremona, January 2024

Presenting the artistic and professional work of one’s father, five years after his death, is an arduous and complex task. Remaining objective in recounting the stories without being influenced by emotions and memories is difficult if not impossible, and lapsing into partisan judgements or some form of hagiography, I think is profoundly human. I have attempted to be as objective and honest as possible, without being overly influenced by the affection and admiration that my brothers and I have always felt towards him. That affection and admiration have never lessened, even when there was bitter conflict within our family. Violin making has been the glue that has always kept us united, allowing us to get through the difficult and complicated times of our lives.

Our father always said that he had the luck and privilege of working with his children, and we had the opportunity to work with him. This personal and professional experience, which lasted more than forty years, shaped us all in character and personality, making us better people. His presence in the shop was calming, and like a lighthouse, he steered us on the right path. He was a guide and an irreplaceable reference point.

Thanks to his immense experience, his ability to solve work problems was impressive; in the face of obstacles, he always managed to find a solution. When situations appeared to be unsolvable, he came up with effective working strategies. His ways of thinking avoided common limiting assumptions and were consequently highly creative. His work approach was fluid and original, never rigid or banal. His solutions were often surprisingly innovative in their simplicity and were formed, within known schemes, in order to develop ways to restructure thought. This mental process led him to devise new strategies and ways of solving problems effectively. New ideas and solutions are often made up of ancient, already known principles and it is only through a thorough study of the past that one has the insight to create alternative paths.

The study of previous experiences was always one of the cornerstones of his research, which was aimed at correctly reinterpreting them. He tended to renew his working style without ever resorting to short cuts, which he said were never useful but often penalizing. One of his mottos was: ‘the first rule of the Bissolotti workshop is to learn how to fend for yourself’. This invitation should not be considered as a sign of abandonment on his part; rather, it was an incentive for us siblings to find our own solutions and to learn to develop our intellect. His approach to life and work was to never give up, which involved having the courage to learn and taking risks.

Francesco Bissolotti was a man endowed with great irony. He was biting and bitter in his jokes, and his comments could be direct and sharp, but he was never offensive. He was intolerant towards any type of prevailing authority, and his inability to defer to authoritarian power was a source of distress and dissatisfaction.

He was keenly interested in the natural world, and he loved the beauty and harmony of shapes. In anything that was common and ordinary, he managed to discover something extraordinary. He could find a way to put any piece of wood to good use, even one of the poorest quality. All of this greatly influenced his work as a luthier, where the use of unusual wood essences, uncommon models and opinions outside the choir allowed him – despite the criticism – to express himself to the fullest.

As a luthier, he explored the challenges inherent in his profession, such as the search for new sounds and the study of varnishes, and he constantly strived for personal and professional improvement. He was extremely attached to classical Cremonese violin making and to its particular construction method; he dedicated himself completely to promoting and teaching it, investing both his time and money. But he was also open to exploring other styles of violin making, such as Brescian lutherie and the models of da Salò, and Mantuan lutherie, especially the works of Camillo de Camilli.

He was one of the most important luthiers of the second half of the last century. In addition to construction, he dedicated himself passionately to teaching countless students. The last time I saw him in our workshop was just before Christmas 2018. Despite being in pain, he was setting the neck joint of his last violin and told me to warm up the glue while he checked the measurements one last time. After glueing the neck, he sat in an armchair and told me about the malaise he was experiencing and he shared his doubts about his uncertain future. His death has deprived us children of a loving father and a reliable guide. At the same time, the world of violin making has lost one of its finest figures.

With this memory, I would like to pay tribute to his work, the fruit of a true and honest artisan who remained committed to his craft until the very end.

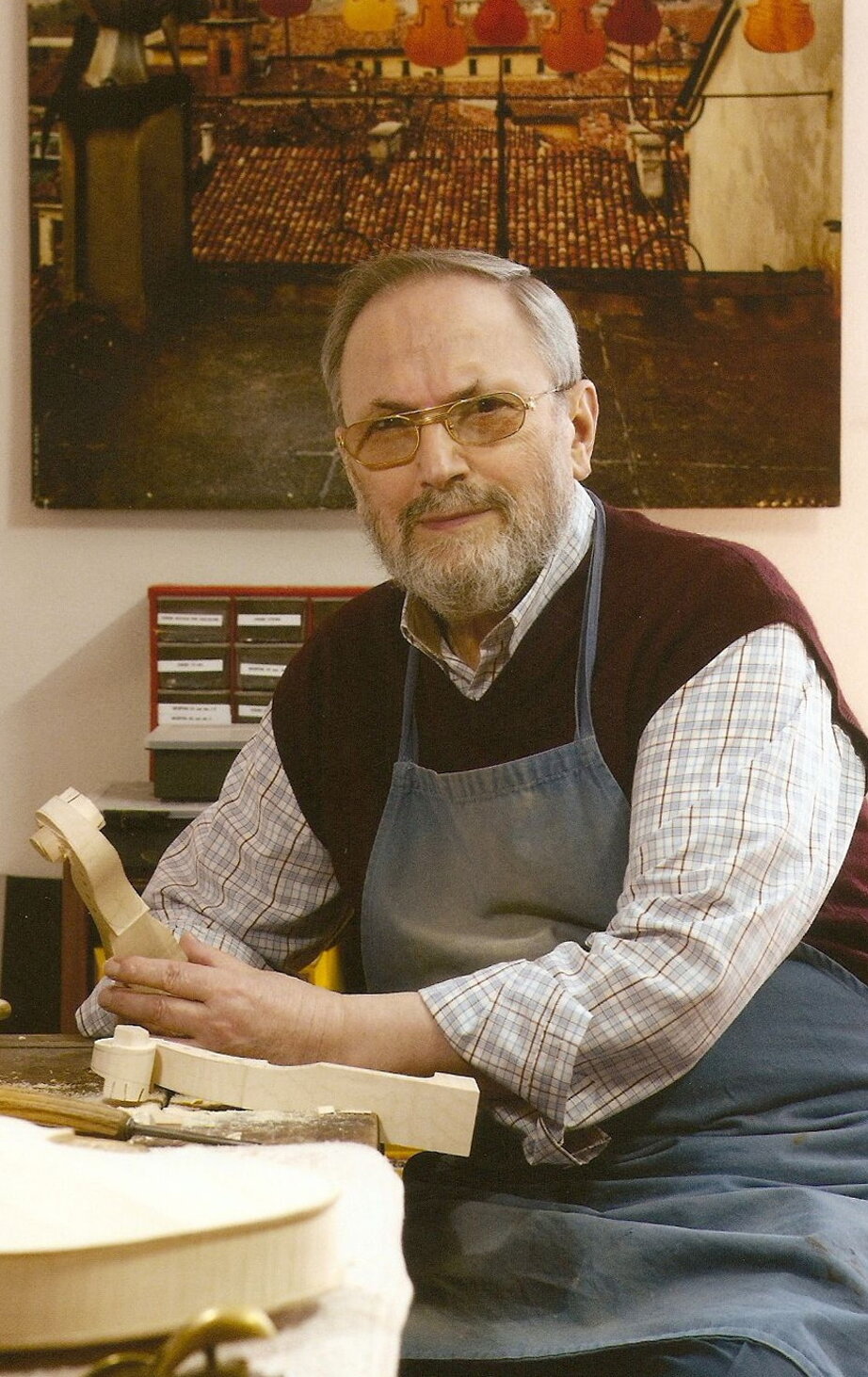

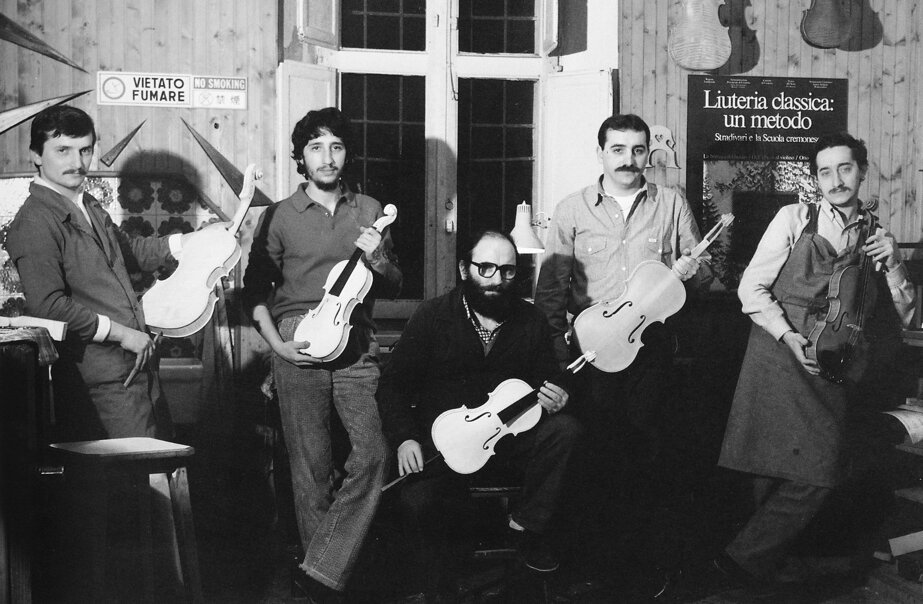

In the photos, from above:

► The master luthier Francesco Bissolotti Photo © 2017 Bissolotti Archive, Cremona

► The master luthier Francesco Bissolotti (center) and (from left) the sons luthiers Vincenzo, Tiziano, Marco Vinicio and Maurizio - Photo © 1981 Bissolotti Archive, Cremona

© 2024 - In memory of Francesco Bissolotti in the 5th anniversary of his death