© 2024 - In memory of Francesco Bissolotti in the 5th anniversary of his death

The Maestro Sacconi

in the testimony of the violinmaker, restorer and expert

Charles Beare

London, July 4, 1985

Link: Charles Beare

I arrived in New York by ocean liner at six o'clock one dark Saturday morning in January 1960. Rembert Wurlitzer had visited London while I was still at the violin making school at Mittenwald, and without even knowing me had suggested to my grateful parents that I spend a year in New York, as he felt that his workshop under Mr. Sacconi had achieved great advances in the techniques of restoration, and anyway I would benefit from seeing large numbers of the world's finest instruments. Any trepidation I felt as I gathered my belongings on the dockside quickly evaporated when a tall, elegant gentleman raised his hat and introduced himself as Rembert Wurlitzer, and by nine o'clock I was at the Wurlitzer premises on 42nd Street, meeting some of the best friends I have ever had.

Mr. Sacconi gave me a warm handshake and a friendly smile, and as I watched him sit down at his bench and remove the table of a 1720 Stradivari that had arrived from Spain that same morning, I realized that I had never imagined a craftsman with such masterly skill: everything he did was speedy and accurate, and to watch his hands that first day was a revelation.

Mr. Sacconi was on the extreme right of the workshop on the mezzanine overlooking 42nd Street. Next to him sat Dario D'Attili, who, as well as being a fine restorer, was responsible for the general running of the workshop and also helped with appraisals: then John Roskoski, a kindly man who was there before Sacconi came; then on the other side of a partition René Morel, Mario D'Alessandro, Hans Nebel, Luiz Bellini (who arrived from Brazil during the year), Vahakn Nigogosian, myself and Daniel Antoun, who worked on bows. Not only the workshop but the whole establishment had a team atmosphere that is seldom seen outside the sports arena, and through the combined skill of its component personalities it dominated the American world of violins. At the head of the team Mr. Sacconi found in Rembert Wurlitzer a colleague of similar ability, with an infallible memory and a unique scholarly knowledge of instruments and their history. Together they made a formidable combination of expertise.

The restoration work that was carried out by Mr. Sacconi and under his direction was of the highest possible standard, far superior to anything I had seen in Europe. In particular there was great respect for original varnish, of whatever quality, and we were called upon always to under-retouch, to lead the eye to areas of unblemished varnish rather than confuse it by matching everything into a homogeneous cloak, a philosophy in stark contrast to that prevailing in Europe at the period. Many things that I had found quite difficult and time-consuming in England were suddenly reduced to simple tasks, because Mr. Sacconi had worked out a logical way of carrying them out, so that time and again one asked oneself “why did no one think of that before?” His treatment of cracks was a case in point, and I learnt that a few minutes extra getting on old crack clean and level can save hours of frustration with the retouching palette.

Much of all this I learnt from Dario D'Attili, and after work or during lunch I would learn more about the great maestro with whom Dario had already worked for twenty years, mainly of his genius, but also of his occasional charming touches of vanity; of his infallible memory for some things, and his dependable forgetfulness of others. I remember going out for lunch one day and seeing Mr. Sacconi upstairs with a customer, puzzling over a violin. We usually lunched together, and Mr. Sacconi called me to say that he would be delayed. In fact he never arrived, and I returned to find him still puzzling, but in a rather agitated state. I was sent to find photographs of the «Pixis» Guarneri del Gesù, and indeed the violin turned out to be a perfect copy of it, except for the varnish, which was unpleasant. A quarter of an hour later Mr. Sacconi descended to the workshop in great excitement: “I made-a the violin, but somebody they revarnish,” he cried. A few minutes later Dario appeared. “Who made-a this violin?” asked Sacconi. “You did” said Dario, with the briefest of glances, “but some idiot revarnished it.”

Quite often a reasonably important Italian violin, even a Stradivari, would appear twice in the shop in the space of a few weeks, and the second time Mr. Sacconi would make exactly the same detailed observations as on the first occasion, but with no recollection of having seen the instrument before. He had a photographic memory for the style and workmanship of particular makers, in Stradivari's case even following the slight changes from year to year, but he had difficulty sometimes recalling a specific instrument with the same details as the one in his hand. In this his mind worked differently from that of Rembert Wurlitzer, who on examining an instrument would quickly observe things about it that resembled a violin seen, say, in Paris a few years before. Nevertheless Mr. Sacconi would frequently startle his colleagues with an instantaneous identification of the maker of an instrument that had baffled everyone else for hours!

These remarkable powers of observation were carried through into the new instruments that he made, and they were with him right from the beginning. Later on Mr. Sacconi told me that he thought he had made about one hundred instruments himself, but I suppose I have not seen more than fifteen or so. Several of them made a powerful impression on me, but none more than a Stradivari copy made about 1948 which would, I think, have looked well in Cremona two and a quarter centuries before. In some of the earlier instruments, particularly those made before the move to New York, he seems to have been so preoccupied with the techniques of producing a copy, complete with artificial age, that the result is in some way stiff: near perfect as a copy, but lacking the unrestrained something-or-other that constitutes a great work of art. Other instruments, including some of the earlier ones, show their maker to have been inspired and artistically freed, rather than restricted, by his knowledge of Stradivari's work.

A few weeks after my arrival in New York Mr. Sacconi came into the workshop with the «Paganini» Stradivari viola, which I recognized immediately, as would anyone who had seen a photograph of the striking appearance of the back. After I had admired it for some minutes I was aware that Mr. Sacconi seemed to be getting great pleasure from my enjoyment of it, and my face went scarlet when I was finally invited to look at the label, «Simone Fernando Sacconi fecit ...».

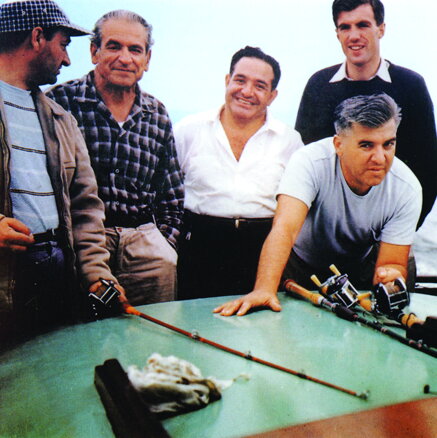

One Sunday we were all invited by a customer for a day's fishing in Long Island Sound. Everyone knew of Mr. Sacconi's fame as a striped bass fisherman, so the pressure was on him to catch something pretty large. My photograph shows the result: a six inch fish accidentally foul-hooked. Years later I took Mr. Sacconi netting for Dover sole on a sandy beach near Dover itself. He duly dragged his end of the net through thigh-deep water and seemed excited by our catch of nine good fish, but I was in great trouble for doing it with a net rather than with rad and line.

Long after I had to return to England Mr. Sacconi, when he came to visit, would help me with his wisdom and advice about repairs, and on occasion he would simply sit down at my bench and finish in two or three minutes some problem that I had been unable to salve. Fortunately I was able to see him at least once or twice a year, and in his last years I would visit him during his stays in Cremona. There he was totally in his element, except for the time when his wife Teresita had had a serious operation involving several blood transfusions.

His worries about her had been lightened somewhat by his being made an Honorary Citizen of Cremona, and I congratulated him warmly. “Why they make him and not me Onorario?” piped up Teresita, ashen faced. “He gotta no Cremonese blood in him at all, I got all Cremonese blood.”

«I 'Segreti' di Stradivari» was Fernando Sacconi's final gift to his profession, a detailed account of how Stradivari made his unique instruments, and it has become almost a bible. The method described in it is, I believe, certainly Stradivari's and almost certainly the best, but Sacconi would have been upset at those who follow it blindly and assume that their result will inevitably be good. He achieved what he did and became the great person that he was by questioning everything, following his own instincts and making up his own mind, and always looking for a better way of doing things, and a better result. Antonio Stradivari himself can hardly have been very different.

London, July 4, 1985

Taken from the book: «From Violinmaking to Music: The Life and Works of Simone Fernando Sacconi», presented on December 17, 1985 at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. (Cremona, ACLAP, first edition 1985, second edition 1986, pages 105-108 - Italian / English).

Simone Fernando Sacconi

fishing with some colleagues on the Atlantic Ocean in Long Island Bay

fishing with some colleagues on the Atlantic Ocean in Long Island Bay

Long Island, in the state of New York, is an island on the east coast of the United States, located opposite the states of New York and Connecticut. It is 190 km long and has a maximum width of 37 km. It is separated from the mainland by the Long Island Sound, a 145 km long and 5 to 32 km wide stretch of sea.

Long Island

In the photo above, from the left:

Dario D'Attili, Simone Fernando Sacconi, Vahakn Nigogosian and Charles Beare.

In the center, in the foreground: Mario D'Alessandro

Pictured below:

Cover of the book «From Violinmaking to Music: The Life and Works of Simone Fernando Sacconi» (English version)

© 2024 - In memory of Francesco Bissolotti in the 5th anniversary of his death