© 2024 - In memory of Francesco Bissolotti in the 5th anniversary of his death

The Maestro Sacconi

in the testimony of the violinmaker and restorer

Luiz Bellini

New York, March 2, 1984

Link: Luiz Bellini

When I was fifteen years old, I went to woodcarving school, where I studied for five years to earn my diploma as a master woodcarver. This meant that I could have taught in government schools, but I never even went to pick up the diploma! During my last year at school my teacher brought in a semi-finished violin of his, so I finally knew that he had been making violins all those years, but had never talked about it! This violin was finished in the white, and he did the fingerboard in school. I was very much impressed by this instrument and wondered if I could make one. I asked him about it, and he said, “Of course you could make one!”

He gave me the measurements, the outline, and some of the details, but not very specific instructions. He was a wonderful woodcarver, but not a professional violinmaker. I left school at that time and made the violin at home. He said to me before I left, “When you have finished it, come back and show it to me. I would like to see it!” Months later I went to see him and showed it to him. He was impressed and said, “Would you like to start learning violinmaking as a profession?”

I liked the idea, but I didn't know if I could, because I was from a poor family and couldn't really afford to start studying all over again instead of working and earning money. When I asked my father, he said, “Well, I don't think that's the right thing to do now. Who is going to buy violins in Brazil? It's better to make guitars than violins!” Anyway, in the end he softened and said, “Well, if you like, try it!”

Then I was so anxious to start I went back to my woodcarving teacher and told him I wanted to meet his friend who was a violinmaker to see if he would like to teach me. He answered, “I'm sure he would, because I already spoke to him about you and he was very excited. He likes to teach somebody his craft.” His name was Guido Pascoli, and my teacher gave me a card introducing me to him. He asked me, “When do you want to start?” I said, “Whenever you want me to start.” He answered, “Why don't you start right now! This will be your bench. Clean it, prepare it, and I'll start giving you the instructions.”

I was so happy about it all that I didn't even discuss if I was going to make money or pay him. We were both very excited. I think he first wanted to know what I was able to do, because after a few days he said, “I feel that you have talent. I will not be able to pay you very much because I will be teaching you, but I will pay you.” I was so happy that I could at least get some money and didn't have to pay him!

I stayed with Mr. Pascoli for five years, and then he told me, “You have learned everything I can teach you. It would be a very good idea if you went to New York to R. Wurlitzer, Inc., where you could work under the direction of Mr. Sacconi.” I had heard of Sacconi, and my teacher knew that he was a great maker. It all seemed like a dream to me, because I didn't know if it would be possible.

Again, there was the same dilemma in my family. Now that I was making a decent salary, I told my father about the idea of going to the United States. He didn't object at all this time and said, “If you think you are good enough to go to an important firm, go right ahead!” I was very happy about it, but I thought about all the difficulties of moving to a different country and having to learn a new language. However, the desire to improve and learn more by being in contact with great instruments was stronger than all my fears. Mr. Pascoli asked one of our friends who is a violinist and collector, Mr. Geraldo Modern, to take my references and application to Wurlitzer when he went to New York. Mr. Wurlitzer replied that they would accept me if I came for at least two years. Less would have been a waste of their time. What wonderful news! I can't remember a happier moment in my life!

I arrived on November 21, 1960, a Sunday. The next morning I presented myself in the workshop. I was so anxious to meet Mr. Sacconi and Mr. Wurlitzer. I was introduced to them and to all the workers, altogether about nine people. I was so impressed by the very nice, warm reception. Since I didn't know any English, Mr. Sacconi talked to me in Italian. It was a funny mixture with my Portuguese, but we were understanding each other from the beginning. He showed me my place at the long bench. “You'll sit here,” he said. He asked me if I had brought my tools, but as I thought to get all the best possible tools in the States, I didn't bring along my old ones. Little by little I started buying tools and making them myself. Mr. Sacconi was very helpful in showing me the kind of tools which were useful for the work that was customary at that workshop. The first day I started already making tools. After two or three days he then gave me my first work, a bass bar far a violin. I don't recall the instrument, but it probably wasn't a very good one. Mr. Sacconi surely wanted to find out how much I knew. I followed his instructions in making the bass bar, and he was so happy with it that he showed it to Mr. Wurlitzer, who came over and said, “Bravo Luigi!” It made me feel so good to know that although I had come there to learn, they still appreciated even the small things I did well.

From then on Mr. Sacconi kept giving me better and better jobs until I reached the level of the other workers and was given some of the beautiful instruments to restore. After five months Mr. Sacconi told me that I should make a Stradivarius model violin under his supervision. As months went by and he had not heard from me about this idea, he started to insist on it. Now I am very happy that I made this violin under his direction in 1961, because I realize how much I learned with him about the particularities of the old master's workmanship.

Mr. Sacconi had a wonderful and intensive drive to teach. As he had arrived at such a high level of knowledge, combined with his skills, he was the perfect teacher beyond the shadow of a doubt. Also, I found that when Mr. Sacconi trusted your ability, he had no reservations. The trust was complete, and he let you use your own imagination while doing a restoration. I must say, however, that even after having worked for almost eight years with him, I hardly ever came up with an improvement over a particular type of repair already established, because Mr. Sacconi was so thorough in all he planned.

He knew even the most minor details of the workmanship of the old masters, especially of Stradivarius. His artistry in retouching antique varnishes was particularly admirable. He had a sixth sense for color and varnish texture superior to anyone I have ever met, and his system of using a palette with basic colors, usually dried pigments, was quite different from what I was accustomed to before I met him. It was a real treat to watch him retouch one of his interesting repair jobs and see the beauty coming through on a back or a belly of a marvellous old Cremonese instrument. He certainly inspired me more than anybody else in my dedication to what has become my first love, making copies of the great masters' works. In this specialized art Mr. Sacconi was, in my opinion, the best and most knowledgeable in the world.

Mr. Sacconi was also so enthusiastic about everything he did that he threw himself into his work body and soul. On top of all the energy he spent creating, and planning work for the others of us, he had a lot of pressure on him due to his position at Wurlitzer. All the same, he would stop the minute anyone needed help or advice, and he was so friendly the way he gave it, too. Then on Saturdays when there were fewer customers and only half of the workers, he talked to us about violins or about fishing (which he loved). He would also tell us stories, like the one about going to sweep the floor in the violinmaker's shop when he was only eight years old, so he could watch him work!

I remember one Saturday in 1962 when he came over to me with a violin in his hands and handed it to me very carefully, saying in Italian, “Luigi, guarda questo Stradivari. È un violino molto interessante!” (Luigi, look at this Stradivarius. It's a very interesting violin!) After I took a good look, I started to make my remarks. “It's really a beautiful instrument, and what a great state of preservation!” Mr. Sacconi, having already savoured his practical joke, told me then, “Sorry Luigi, but it's a copy I made in 1935.” Then he left apologetically, but smiling. He enjoyed those little things.

Mr. Sacconi made incalculable contributions to the world of violinmaking, as an unparalleled expert in appraisal and restoration, and as a teacher of unique capacities. Now that I look back, I can't stop thinking how lucky I was to have worked in the shop with him!

New York, March 2, 1984

Taken from the book: «From Violinmaking to Music: The Life and Works of Simone Fernando Sacconi», presented on December 17, 1985 at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. (Cremona, ACLAP, first edition 1985, second edition 1986, pages 115-117 - Italian / English).

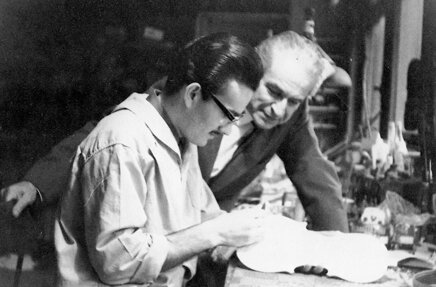

Luiz Bellini

and Simone Fernando Sacconi

Luiz Bellini (in the foreground) at the workbench, assisted

by Master Sacconi.

© 2024 - In memory of Francesco Bissolotti in the 5th anniversary of his death