© 2024 - In memory of Francesco Bissolotti in the 5th anniversary of his death

The Maestro Sacconi

in the testimony of the violinmaker, restorer and expert

Vahakn Nigogosian

New York, March 1, 1984

Link: Vahakn Nigogosian

Seventy-five years ago my father founded the first vocational school in Turkey. He was very much ahead of his time and therefore always had troubles, but he managed to add craft workshops to the regular school subjects: woodwork, ironwork, shoemaking, gardening, cooking, etc. These courses turned out to be very important later in my life.

The woodworking class was really what led me to take up violinmaking. One day I asked my father to buy me a violin, and he said, “I don't have enough money to buy a violin, but if you want, I'll buy the wood and you can try to make your own violin.” At that time I wanted to become a mechanical engineer, but I later changed my mind and became a violinmaker.

This was very hard for me, because in Turkey nobody knew how to make violins, or if somebody knew something, they didn't want to teach it. When I began working on my first violin, I didn't even know how to bend the ribs! I had to make my own tool to bend them, and finally managed to make the violin. Then my father took me to a druggist friend in Istanbul who was an amateur sculptor and also made violins, but kept everything secret. When he saw my violin he thought I had copied a Czechoslovakian gypsy violin, because it had no corners, corner blocks, or neck block. He took me on, but he was so busy that every time I needed to ask him something I had to wait half an hour, or even an hour! All the same, I made two more violins, and showed my third to Jacques Thibaud, who encouraged me to go to France.

I went, hoping to be able to work, but the French violinmakers asked me to pay them because they had to teach me. My father wasn't able to help me, so I was lucky that I had studied in his school and managed to support myself making shoes and Turkish candy while I studied with Marcel Vatelot for three and a half years. Then I went back to work in Turkey, but after twenty-five years I decided to leave the country because of the political problems between the Turks and the Armenians.

I asked Marcel Vatelot and Pierre Fournier if I could go to the Wurlitzer Company, which was the best in the world at the time. Sometimes they had as many as ten to fifteen Stradivariuses there at once. I did get to Wurlitzer in 1958, and when I arrived I didn't know any English, only French, Turkish, Armenian, and a little Greek. Mr. Sacconi and some of the other workers knew French, which helped me a lot at the beginning.

At first I was put in the back and got all the bad instruments, but I knew I had to be patient. One day I had to do a repair job on an old viola, and what I did was all right, but it changed the sound of the instrument, and the prospective buyer didn't want it anymore. I understood that the tension had changed when I repaired the top, which had sunk about 7 millimeters, so I asked Mr. Wurlitzer to let me try to reduce the tension by raising the saddle. It worked, and from then on if there was some kind of problem, Mr. Wurlitzer let me do what I wanted. That caused some friction in the shop, because I had just arrived, and the others had been there for ten years or so. Anyway, little by little they gave me more difficult jobs, which was challenging for me, and I stayed on for ten years. Then Mr. Wurlitzer died, things slowly started to go wrong, and four of us decided to leave. It was a shame, because while they were alive, Mr. Wurlitzer and Mr. Sacconi were able to get good workers and made sure that the instruments always turned out in perfect condition.

Sacconi, himself, was the greatest repairman, in my opinion. He was so cautious in character and in his work that he closed all the doors to possible mistakes, and he insisted that everything be done just right. He was great, not only because of his high standards, but because he had a beautiful eye, and not even the smallest detail escaped him. I appreciate so much what he did, because he served as a guideline for all of us, and if we succeeded, it was thanks to his example. I remember one time when he had to do the terribly difficult job of patching the whole back of a Guarneri that had been eaten by worms, and when he showed it to me after two months of work, I couldn't find any part of the repair, it was so perfect.

Sacconi studied Stradivarius all his life. In fact, he was such a fanatic about Stradivarius's work that he even named his boat «Strad»! He knew an incredible number of details about Stradivarius's work, such as how he sat to do the purfling! Most important, he knew the character of the instrument, and of the varnish. Once he was the only one in the shop able to recognize two Strads from which the characteristically beautiful varnish had been removed, because without the old Italian varnish there's not much left.

Once I told Sacconi that when I looked at his instruments, I saw Stradivarius instead of him, and he answered, “You know Nigo, thirty-five years ago they told me the same thing. I tried doing things differently, but I found over and over again that Stradivarius's way was the best.” After having seen so many Strads, I believe he was right. In his work you see how many different things he tried, and when he saw that something was wrong, he turned back and tried something else. Stradivarius was such a genius that he was able to make perfect instruments even with the old methods. His work was so exceptional that you wouldn't even notice certain considerable irregularities, such as the 4-millimeter difference between the corners of one of his cellos, if you didn't have measuring instruments.

Other old Italian masters of lesser importance used the same methods, but their work was so imperfect that I would not have hired them in my shop. A modern violin made like these would have a bad sound, and the only reason these sound good is that the wood has vibrated for so many decades. Others of the same epoch that have not been played do not sound as good. All this I learned while working with Sacconi.

Sometimes we discussed the work that was to be done, but he didn't really like to do this. I remember when we had to make an emergency repair on the Amati cello of the Juilliard Quartet. They gave the neck to Bellini, the top to René Morel, I think, and I got the back.

It had a big crack under the sound post and another one close to it, besides being deformed. Usually you push in deformed archings, but I had to figure out a special technique because of the cracks. Mr. Sacconi didn't want to let me try the idea I had, because he was convinced that it wouldn't work, but I'm a hard-headed, stubborn Armenian, and got permission from Rembert Wurlitzer to go ahead with it. Luckily it came out perfectly, and Sacconi was happy with my work, even though he had been sure that I would wind up with a hole in the instrument.

We didn't always agree on the type of sound an instrument should have, either. He always liked to force the violin a little, pulling everything he could. Sometimes musicians had difficulty with his set-ups, which he made a little high, making the response of the instrument slower, and causing the musician to have to press harder. However, he accepted my method of changing the pressure by raising or lowering the saddle.

I respect Mr. Sacconi very much. There are very few artists like him. His mind was always on his work, not on money or other things. He didn't always have an easy time, because he reasoned like an artist, not in business terms. Sometimes he didn't realize certain practical things, like how long a job would take. He was also a little old-fashioned in his fear of the boss. I once told him, “You have the capacity, he has the money, and your capacity is as valuable as his money, if not more. What are you afraid of? You are Sacconi!” He was sensitive and vulnerable, though, und I think certain circumstances caused his early death. Shortly before he died he explained his situation to me and then started crying. Now it is too late, and I don't want to open old issues, but I still feel very angry about his end. His work is always in my mind, though, and I know his life's work is still important to all of us.

New York, March 1, 1984

Taken from the book: «From Violinmaking to Music: The Life and Works of Simone Fernando Sacconi», presented on December 17, 1985 at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. (Cremona, ACLAP, first edition 1985, second edition 1986, pages 99-101 - Italian / English).

Vahakn Nigogosian

and Simone Fernando Sacconi

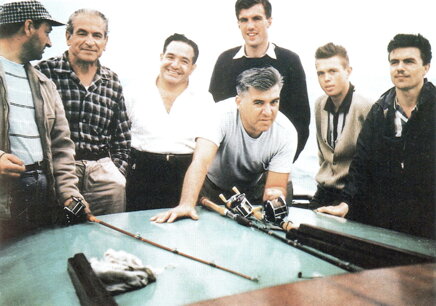

Vahakn Nigogosian (third from left in the picture) with the Master Sacconi, second from left.

© 2024 - In memory of Francesco Bissolotti in the 5th anniversary of his death